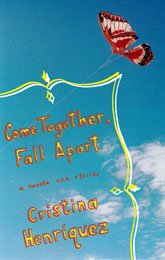

Crstina Henriquez, or cek as we lovingly call her, Workshop class of Ought Three, is the author of the highly praised story collection Come Together, Fall Apart. No less a pantheon member than Isabel Allende says this about it: “These stories, told in a direct and sparse style, are truly unforgettable. Cristina Henríquez's young female protagonists are as haunting as the setting of Panama. I could not put aside this book." All well and good. But what about Sandra Cisneros? Well... "How does a young writer gather the wisdom, heart, and tenderness to write stories of such exquisite humanity? I can only guess she is an ancient soul, a zen master, a bruja, or all of the above."

Crstina Henriquez, or cek as we lovingly call her, Workshop class of Ought Three, is the author of the highly praised story collection Come Together, Fall Apart. No less a pantheon member than Isabel Allende says this about it: “These stories, told in a direct and sparse style, are truly unforgettable. Cristina Henríquez's young female protagonists are as haunting as the setting of Panama. I could not put aside this book." All well and good. But what about Sandra Cisneros? Well... "How does a young writer gather the wisdom, heart, and tenderness to write stories of such exquisite humanity? I can only guess she is an ancient soul, a zen master, a bruja, or all of the above."Let's have a nice, long chat with America's hottest young Latina writer, shall we? Pull up a chair and grab some coffee.

EG: Your book is getting glowing, even breathless, reviews . Way to go. Did you work on these stories in Come Together, Fall Apart at the Workshop? How long did it take to write them and were they published in magazines prior to the book?

CH: The only story in the book that was workshopped is "The Box House and the Snow," which was a story I wrote before I got to Iowa and then submitted for my first workshop (Grendel, I still have your comments on it), although it was in a much different form back then. Otherwise, I wrote only one other story from the collection while at Iowa: "Beautiful." I wrote it the first week I was there, when the reality of going to graduate school was sinking in, and I thought I had better get to work because I was sure that everyone else in the program was more talented than I and that they already had a lot more stories under their belts. I wrote it in a creative frenzy that lasted about three days.

But after that, my time at Iowa was spent working on all sorts of stories set in the United States. "Mercury" is the earliest-penned story, written when I was an undergraduate at Northwestern. And, except for those three, I wrote everything else after Iowa, when I had time to clear my head a bit, when I was just sitting around after we had moved to hot, hot Dallas and I didn't have any friends yet nor even a car to get me out of the house. So all in all, I wrote these stories over a period of about five years, but I was working on other things in the meantime that didn't make the cut.

"Beautiful" was published in TriQuarterly; "Drive" in the Virginia Quarterly Review's special issue called Fiction's New Luminaries, which includes stores from some other Iowa grads; "Mercury" in Glimmer Train; "Ashes" in the New Yorker; and "Chasing Birds" in Ploughshares. That list reflects the order in which the stories were accepted over time.

EG: Can you tell us the story of how your book came to be published?

CH: I'm not sure how far back to start, but basically after I left Iowa, I got an agent and started thinking about shaping a collection. I had some stories set in the United States featuring American characters, and I had some stories set in Panama featuring Panamanian characters. My agent, who is amazing, encouraged me to think about which direction I wanted to go, which set of stories I liked more. I took a good look at all of them and it turned out that the stories set in Panama were just BETTER. The characters were more realistic, more alive, the plots felt less forced, that sort of thing.

For some reason, many of my American stories at that time felt a little cartoonish, very exaggerated and just silly. Which wasn't all necessarily bad, but I hadn't yet figured out a way to make cartoonish, exaggerated, and silly add up to a good story. So I decided on Panama and as soon as I had that path laid out, I worked to round out a collection with more and more stories set there. When I had it all together, I thought, great, it's ready to go.

But then my agent and I discussed the possibility of my writing the start of a novel (she knew I had an idea for one) that we could send out with the collection, to try to get a two-book deal, which is strangely supposed to be easier than getting a one-book deal. So I worked on a novel for a while until I had 100 pages. We did a few rounds of fine-tuning everything and then she went out with it all. The first publisher we heard back from was Riverhead, literally two days after she had starting sending everything out. And I gasped when she told me Riverhead was interested. Because they were definitely one of my dream publishers. They publish what seems like half of my favorite authors. But then another publisher was interested, another passed, on and on it went for a few more days until we had gotten all the bids we were going to get. There was some negotiating. My agent kept me updated. And then I ended up at Riverhead, with an editor and whole team of people who have been extremely good to me. They're incredible.

EG: You have had two -- TWO -- (2) -- dos -- stories published in the New Yorker so far ("Ashes," July 4, 2005 and "Carnival, Las Tablas," July 3, 2006), which is quite unusual for someone of such a relatively tender age. Do you think you'll eventually catch up with John Updike? How did it work getting your stories into the New Yorker? What was the editing process like there?

CH: Oh, I'm going to leave John Updike in the dust. I have a carefully plotted forty-year plan for how to accomplish that. (Reader, do not doubt the existence of this "plan." -- Ed.) Ha! No, it's been one of the very high highlights of my writing career so far to have had two stories published in the New Yorker. "Ashes" was a complete shock. I had sold a few stories by then, but I certainly still assumed the New Yorker was a ridiculous long shot. I had this idea, though, that I should start at the top of the magazine food chain and work my way down because, well, you just never know. I remember Elizabeth McCracken saying that to us once in workshop.

My agent had submitted "Ashes" in the fall and it wasn't until the following spring that we finally heard back that they were taking it. I was working a full-time job then, so my agent emailed me at work: "Call me." My immediate thought was that Riverhead was backing out of the book deal (which we had secured only weeks earlier) or that something equally bad was happening. But I called her and the first thing she said was, "You're going to be in the New Yorker." Predictably, I freaked out. I was running up and down the halls and calling everyone I knew using my work phone and trying to catch my breath. It was fantastic.

"Carnival" was a very different experience, not insofar as I was any less thrilled, but it wasn't so out of the blue. I had been working on that story for a very long time. We submitted it once in a different form and they basically said, it's not ready yet but we'll be happy to read it again if you revise. So revise I did. It was still more or less the same freak out when I found out they were taking it, but I was a bit more prepared for the possibility.

The editing process both times was hands down the most intense editing I've experienced in my life. And both times, I came away from it feeling like I had learned so much. First, Cressida Leyshon (the editor I work with there) looks at the story and suggests changes. They're not so much plot things as line edits, although at times she will say, explain this more, show how this relates to this, that sort of thing. Then a copyeditor gets his or her hands on it and makes a bunch of little changes, a lot of which are simply getting the story to adhere to house style rules (for example, they spell vendor as "vender"). Each time, I see a proof and tell them which changes I accept and which I reject. Then Deborah Treisman submits her edits, of which (for me, at least) there are many. Some of it is really amazing, watching how a sentence can be fine-tuned, for example (I know, I'm not exhibiting that fine-tuning in this interview), or how things might be rearranged for maximum impact. I'm sure there are some authors whose stories don't get as marked up as mine do, and I'm sure there are other authors who aren't really keen on such heavy editing, but for me, it's wonderful.

The other thing I want to say about the process is that you're assigned a fact-checker. Yes, even for fiction. My first fact-checker really went to town on my story. He was calling the Panamanian Embassy and the Smithsonian and lugging books out of the New York Public Library that referenced something in the story. We talked at length about whether chlorine or bleach was a more appropriate cleaning product for the father in the story to be using. The fact-checker was really good about saying, if you mean this to refer to a real place, then I have to fact check it, but if you intend it to be made-up, then I won't worry about it. He also looked for issues of continuity. The one I remember best is that when the mother in "Ashes" sits down on a chair cushion, I had written that the cushion wheezed but, he pointed out, a few lines earlier I had described the same cushion as being completely flat. He blew my mind. But he was great.

EG: What writing advice do you have for young writers hoping to succeed in story-writing?

CH: The first thing I would say is to read as much as you can. Read short stories and novels and nonfiction and poetry. Read stuff that someone recommends even if it doesn't sound like something you would normally be interested in. Just read. A lot.

The second is to be patient. Understand that success is not going to come overnight, whether success for you means finishing a story you love, or getting published. I remember once reading in an interview with George Saunders that he didn't write a story he liked until he was 30. That was very inspirational to me -- the idea that even for a brilliant writer like him, it could take years and years to figure out what the heck he was doing or wanted to do. I mean, I'm young. I know people might look at me and think that the successes I'm finding these days just happened -- presto! -- but I've been writing stories for ten years now, and it's only in the last two or so that I've really had anything to show for it, anything that I even liked. I think it's important for writers who are just starting -- no matter their age -- to know that, to not to have any illusions about what the writing life is going to be like.

EG: What would you say you gained from your time at the Iowa Writers' Workshop?

CH: Man, Iowa gets such a bad rap sometimes. But I had a great time there. It was amazing to be part of a program whose basic philosophy was, here, we're giving you two years to write and not worry about much else. I mean, when in your life will you ever get that again? So I took it really seriously. I set my alarm clock and woke up every morning to write for a few hours and I read in the afternoons and by the time I left two years later I had really practiced writing in a way I never had before. So, for me, the most important thing was that time to practice, practice, practice what I thought I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

Admittedly, I wrote a lot of awful stuff while I was there. But all along I thought that was sort of the point. I saw Spike Lee on Inside the Actors Studio giving advice to the students in the audience, and he said, "Make a lot of mistakes. " His point being that while you're in school, while you have the support of other students and teachers around you, it's the perfect time to make mistakes because people will be there to catch you. It's a good time to try things that may or may not work out, just to see what you're capable of. So I did a lot of that. I wrote a lot, and most of what I wrote were failed stories, but that was okay, even necessary, to be able to come out on the other end with a better sense of what I was not so good at and a better sense of what I was.

Iowa also gave me a sense of purpose and seriousness. I didn't truly start to think, until I got there, that maybe writing was something I could do as a career. I had never before been around so many people who cared so much about writing and who were trying to make a go of it. I gained a sense of craft, as well -- which might seem obvious. I have a few notebooks that I still go back to when I want to look up something Elizabeth said about minor characters or something Frank said about process or something Chris said about dialogue. And I gained friends, some of whom are readers for my work now. And I gained a deep, deep love for Iowa City, which was totally unexpected. I had moved there from Chicago, thinking I was a city girl at heart, and then I ended up adoring Iowa City. I still think that one day perhaps I'd like to get a summer house there, a place where I can sit on the porch and look out at nothing but fields and mosquitoes and the setting sun. There's just something about that place that makes me feel really at peace.

EG: You have focused on Panamanian culture so far in your writing. What is it about Panama that is so compelling to you, and can you tell us a bit about your connection to that place? Is your book being translated into Spanish? Have you had feedback from Panamanian relatives?

CH: I'm half-Panamanian. My father is from Panama. I was eight months old the first time I went, and I've been going for a few weeks almost every year since. All of my dad's family still lives in there, so we stay with family when we go -- for most of my life it was with my grandparents in a neighborhood called San Francisco, and for the past few years it's been with my aunt and uncle and cousins and grandmother (she relocated), who all share one house.

I've been to a number of locales within Panama, but most of my time has been spent in Panama City, doing day-to-day sorts of things like accompanying my grandmother to the doctor and dropping off clothes at the cleaners and going to the grocery store. Because of that, I feel like I have a unique perspective on life in Panama. I'm still an outsider in many ways, definitely, but I've been privy to an insider's perspective in other ways. I actually think that distance has something to do with why writing about Panama works for me. There's enough space between me and Panama for my imagination to take flight. I have some breathing room.

The book hasn't been translated into Spanish yet, but I do know of a bunch of Panamanians who have read it. I've received emails from people living in Panama who have recommended it for their book clubs there, which I love to hear. My cousin has told me that certain characters remind her of people she knows, that someone will make a gesture that only a Panamanian would make -- in other words, that I'm getting things right -- which is immensely gratifying.

In nearly every city I visited on tour, at least one Panamanian would be in the audience, which was always a thrill for me. One girl even knew who my grandfather was. They all seemed to like the book. Someone said that I was sharing Panama with the world, and that sort of freaked me out, because I felt the sudden weight of responsibility, something I'd wrestled with ever since it was clear that I would put together a collection of stories set in Panama. But to hear someone verbalize it, and in such a hopeful way, was scary.

I try to remind myself, though, that my responsibility is not to Panama, per se, but to each individual character and story. Actually, that came up in a more negative way when I was in Panama last year and I went out to dinner with a family friend, who told me she had read the story "Drive." I asked her what she thought about it, and it turned out that she was fairly offended by it. The story features a drug-dealer boyfriend and a narrator who goes to some extreme lengths not to have children, and she started asking me whether that was really how I thought of Panamanians and railing that all Panamanians weren't like that. I told her that I knew that, that they were just characters, meant to represent only themselves, not an entire population. We went back and forth for a few minutes and eventually agreed to disagree, but I doubt she's happy about it to this day. I guess there will always be those reactions. But what can I do? I'm not trying to capture all of Panamanian society in a story, or in a book. I will probably never make the tourism board happy. But that's not my job.

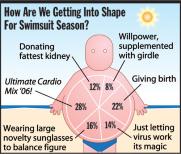

EG: Did you see the recent survey that found Panama to be one of the five happiest countries in the world (Columbia and Costa Rica were in there, too)? Did that surprise you?

CH: I haven't seen that survey! Where is it? (Here. -- Ed.) In a way, I'm not surprised at all. Almost everyone I know in Panama is struggling, but they are happy. They feel like there are certain things they will never have, but I bet if you asked them, they would still say overwhelmingly that they have a good life. The people I know aren't overworked like Americans are. They put more emphasis on enjoying life, enjoying their friends, spending time with their families, than they do on work. Compared with people I know in the United States, people in Panama have much more joie de vivre.

EG: How do you like living in Dallas? Do you have a day job there? What is Ryan up to these days?

CH: There are some things about Dallas that are great -- the gym I belong to, so many sunny days, certain restaurants, my friends, margaritas, the fact that almost every store on earth has a location here so I never have to order things online and pay for shipping. But I would love to live somewhere again where I don't need a car. And I would love to be near at least one really great independent bookstore (Prairie Lights spoiled me!). And I would love to be closer to my family. So I don't think I'll be here forever.

I don't have a day job beyond writing. I do things here and there -- I was teaching at the University of Texas at Dallas, and I help out with the Arts & Letters Live literary festival, and I mentor a few people one-on-one. But for about the past year now, my real full-time job has been writing. Which, I don't think I need to tell you, is insanely, undeniably awesome.

When we first moved here, I got a part-time job working at an independent movie theatre (the Magnolia) in town. I worked there for about three months, shoveling popcorn and tearing ticket stubs, and sweeping up mustard packets after the show. I used to jot down lines for stories on the back of the printed movie schedule we would get each day. I would be standing up at the host stand between films, writing down random lines. Actually, the beginning of "Drive" came to me that way. I wonder sometimes whether I should get that job back because I wrote some of my favorite stuff while I was working there. Maybe there was some weird collusion going on between my brain and being in the theatre.

After that, I worked at the NPR/PBS station here for about a year. I would write on my lunch breaks and at night sometimes and every Saturday and Sunday morning. It was exhausting, but every writer I know has a similar story. If you really want to do it enough, you cobble your life together to make it happen.

Ryan is still working at Travelocity, where they love him and have told him they want to make Ryan clones.

EG: Last I heard you were working on a novel. How is that going? Do many -- or any -- short story skills transfer, do you think, or is a novel a completely different beast to you? Did your wonderful novella "Come Together, Fall Apart" provide some training?

CH: Oh, my novel! I've told myself that when anyone asks, I'm just supposed to say, "It's fine," and leave it at that.

It's fine.

Actually, it's hard to tell. I definitely definitely feel like I have no idea what I'm doing. Short story skills like dialogue, I guess, transfer, but not much else. Or not in my experience so far anyway. Maybe there are more cunning writers than I who can figure out how everything they learned before is now applicable to this other form, but I haven't been able to do that. Even the novella wasn't good preparation. Part of that is because I don't know where that novella came from. I literally sat up one morning and had the idea, fully-formed, just come to me. I wrote the whole thing in sort of a daze. I wish I could remember better how I was able to plot everything out and move forward through time, etc. because it might really help me now.

That said, there are a few things that I've written in my novel effort so far that I really love, that I think are really working. And I trust I'm going to work everything else out with time. As Frank used to say: Have faith in the process. I know that feeling like I don't know what I'm doing is just part of the process. But writing a novel, some days it feels like jumping off a diving board without being sure there's water in the pool.

EG: What are you reading these days?

CH: I've recently read a whole slew of books that I thought were really great. Predictably, I'm reading mostly novels to try to learn from them, study how they hold together, that sort of thing. Gilead by Marilynne, of course. The History of Love by Nicole Krauss. Small Island by Andrea Levy. I just read Miss American Pie by Margaret Sartor, which is a girl's recovered diary from the 70s, mostly as research for my novel, but I liked it very much. George Saunders' newest book In Persuasion Nation. Ishiguro's Never Let Me Go. Fun Home by Alison Bechdel. Oh, and The Scavenger's Guide to Haute Cuisine by a friend of mine, Steven Rinella, which is a nonfiction book about trying to recreate a forty-five course meal using recipes from the great French chef Auguste Escoffier. The kinds of ingredients he had to get -- and the lengths he had to go to to get them -- is crazy. To answer your question, though, right now I'm in the middle of Veronica by Mary Gaitskill. Otherwise, I'm reading various blogs and trying to Google the answers to crossword clues I can't get.